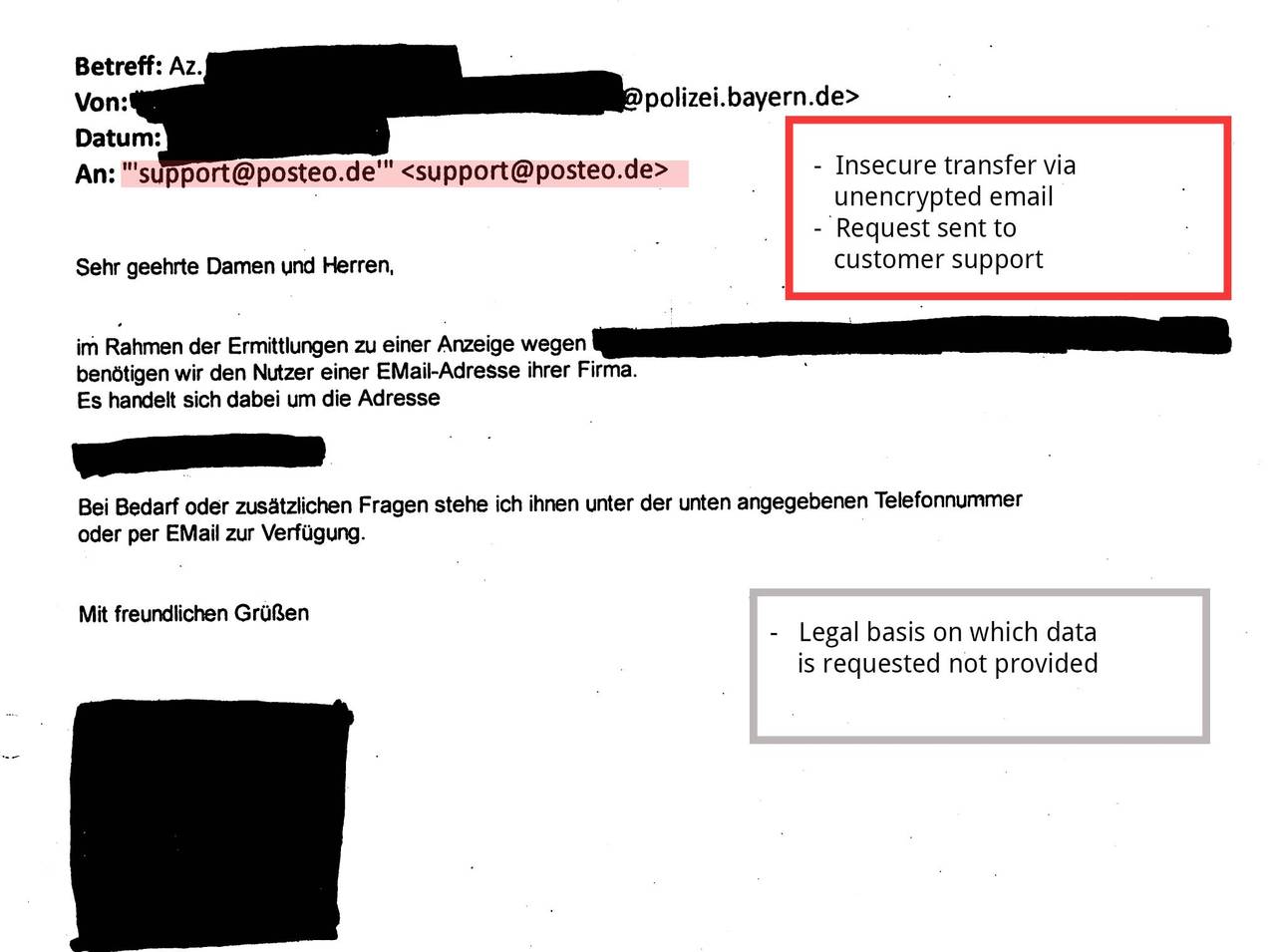

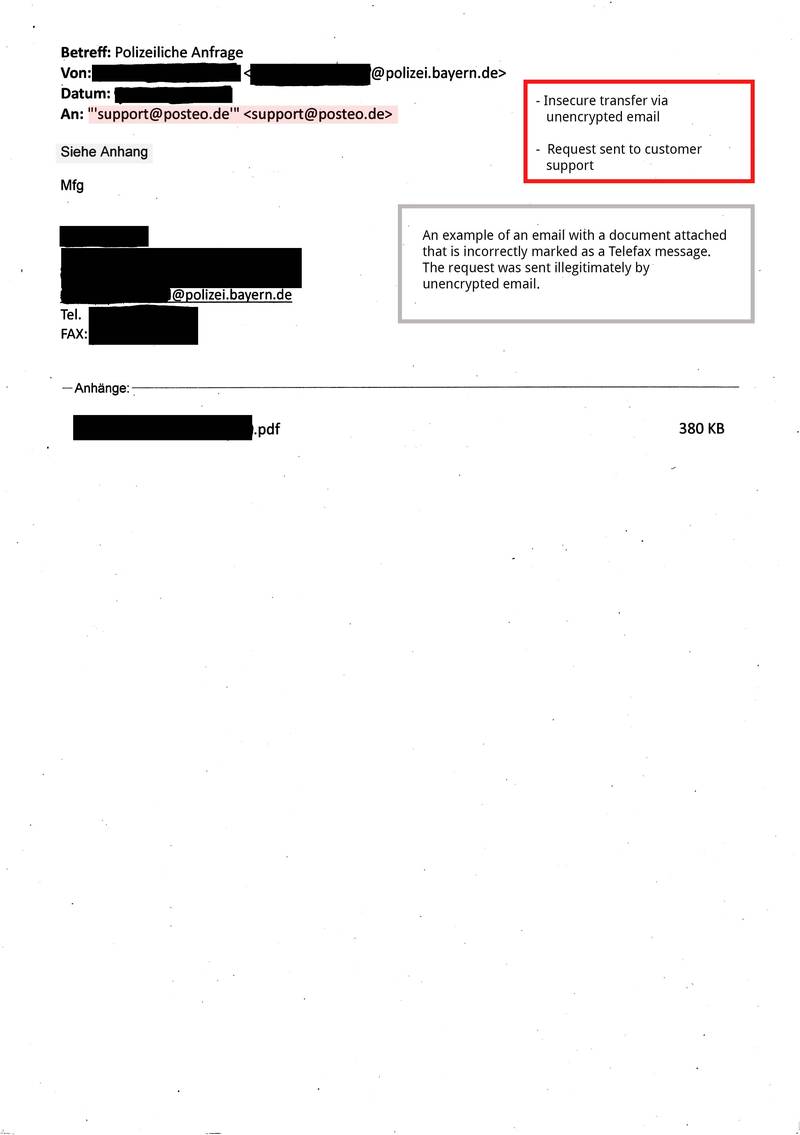

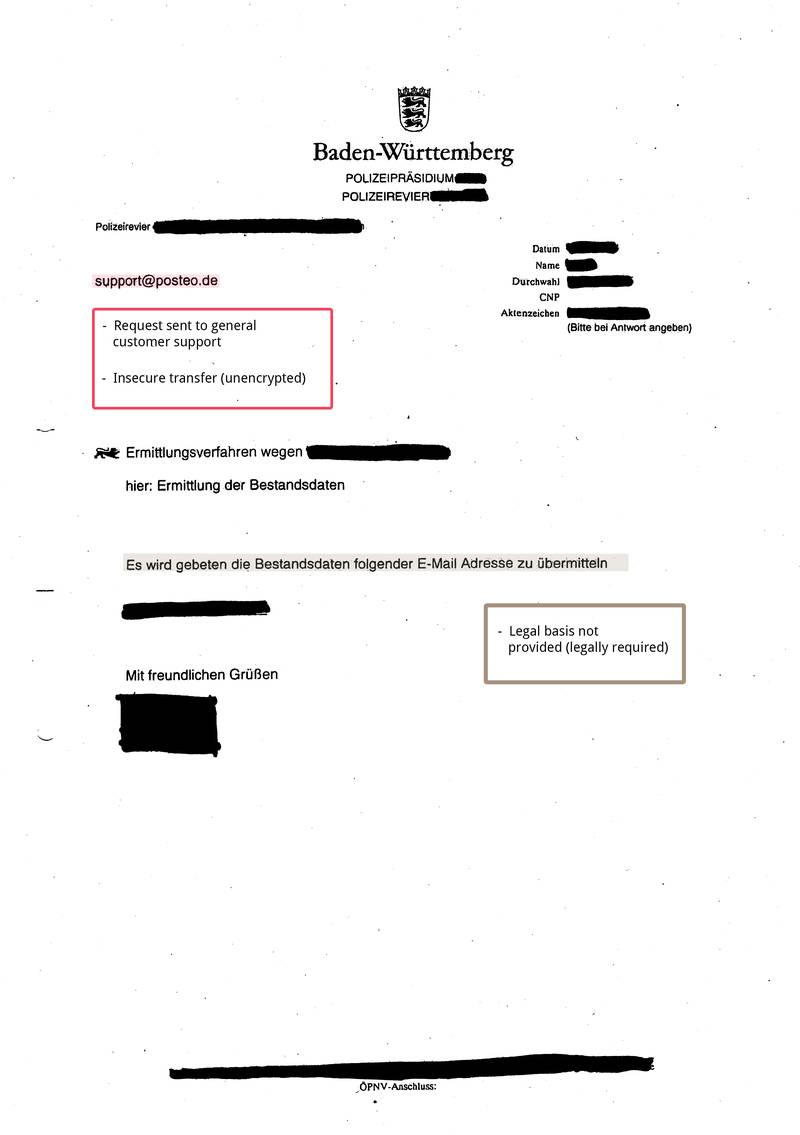

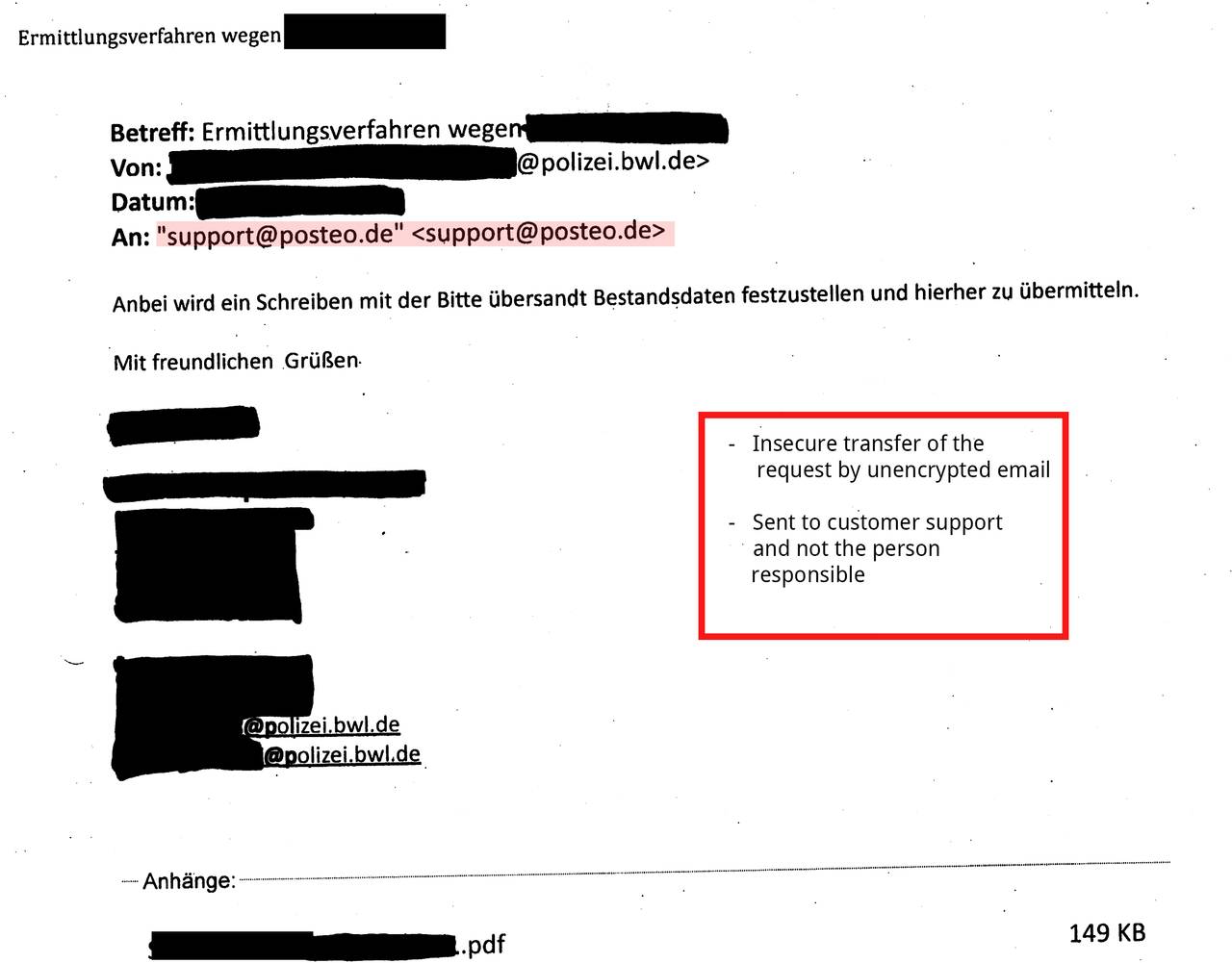

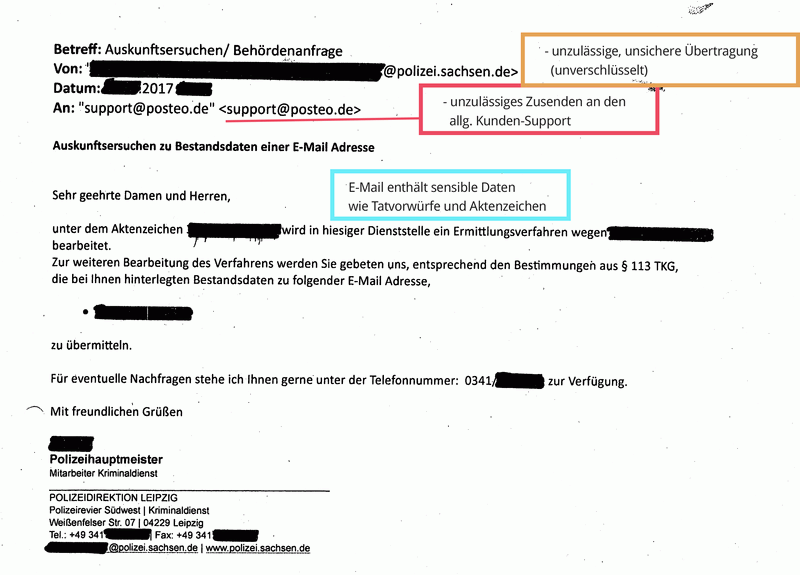

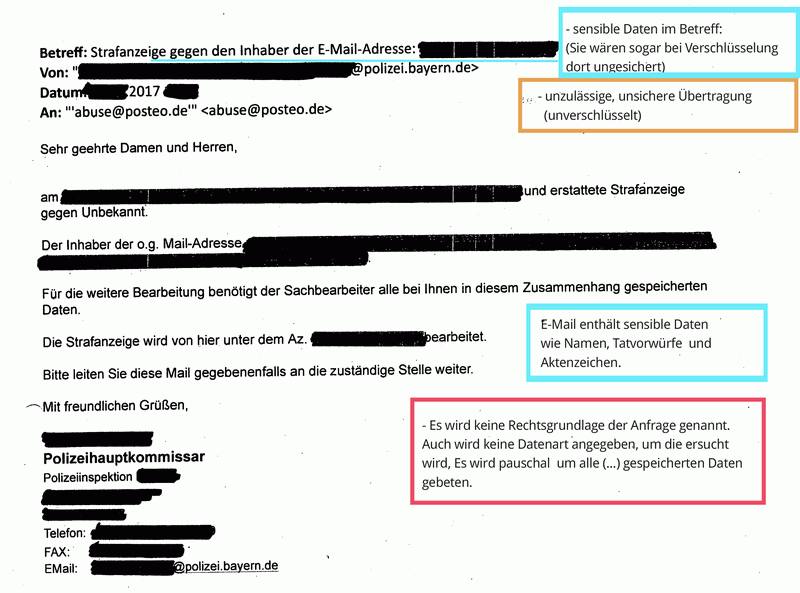

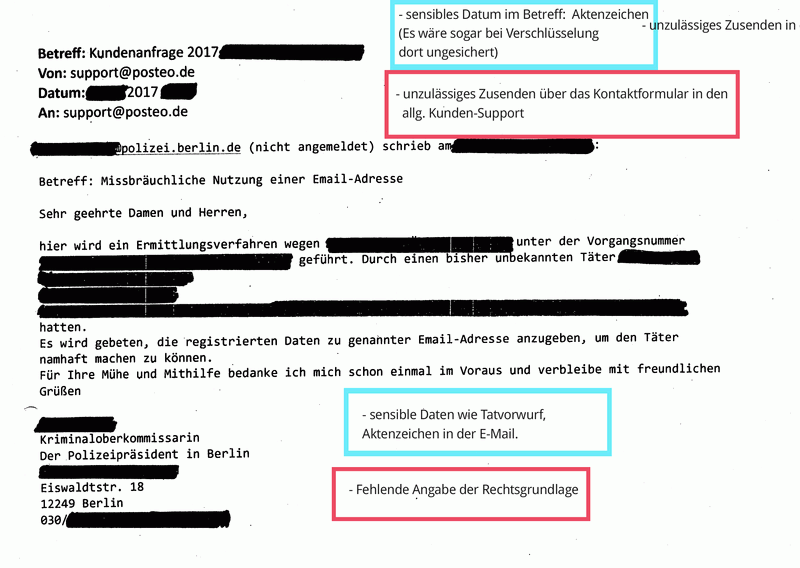

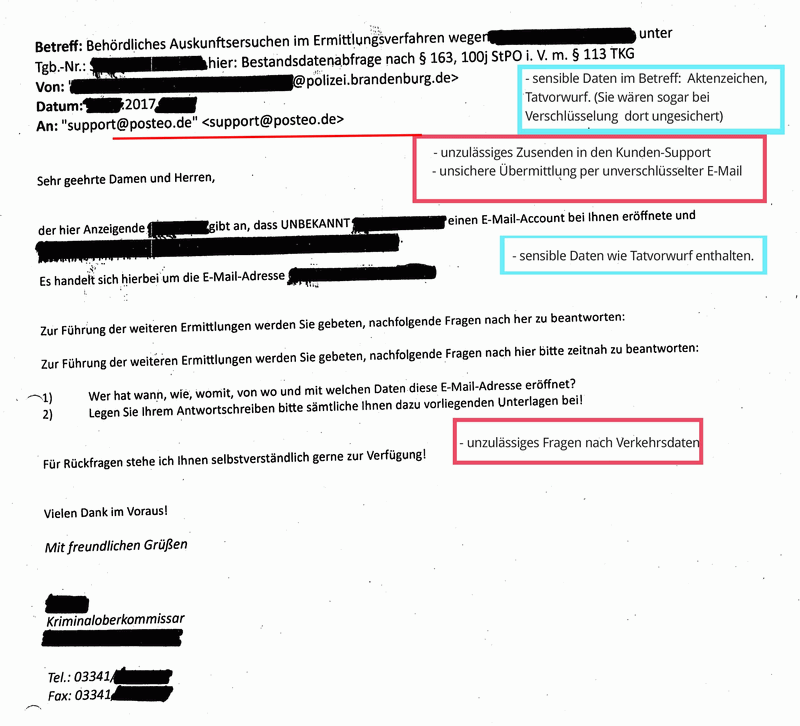

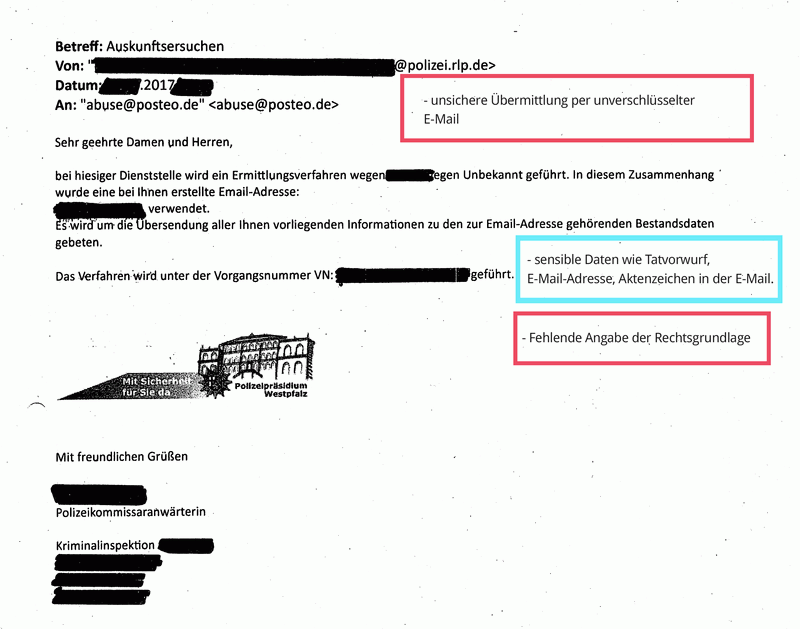

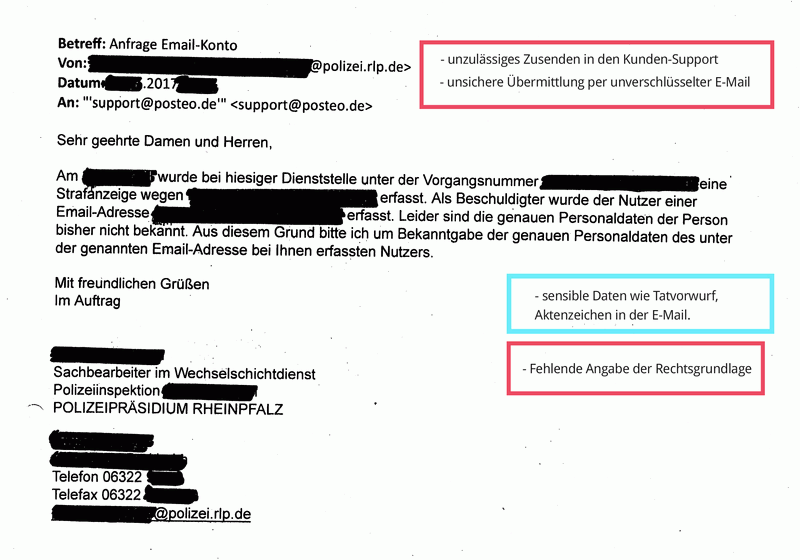

In the practice of requests for information under § 113 TKG there are serious security problems. Requests for user information under § 113 TKG contain sensitive personal information. From police authorities, we mostly receive email addresses or names that are specified in connection with a concrete criminal charge. Sometimes the requests even contain a person’s complete bank or payment details. Posteo frequently receives such requests for user information.

Investigative authorities are legally required by the BDSG (among other things) [translation] to ensure that personal data can not be read, copied, changed or deleted in an unauthorised manner under electronic transfer, during its transport or saving to a data storage medium. (BDSG, Addendum, sentence 4)

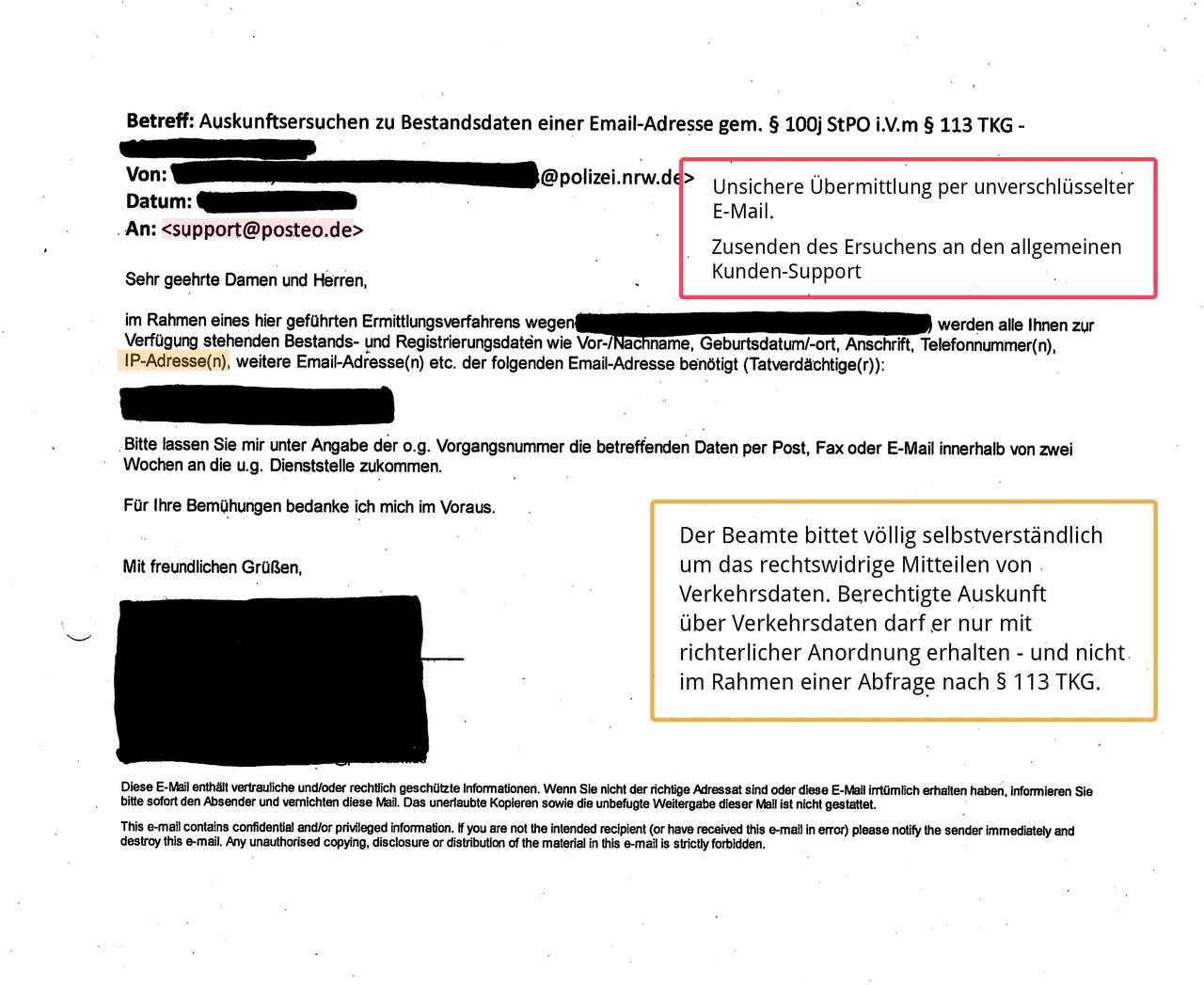

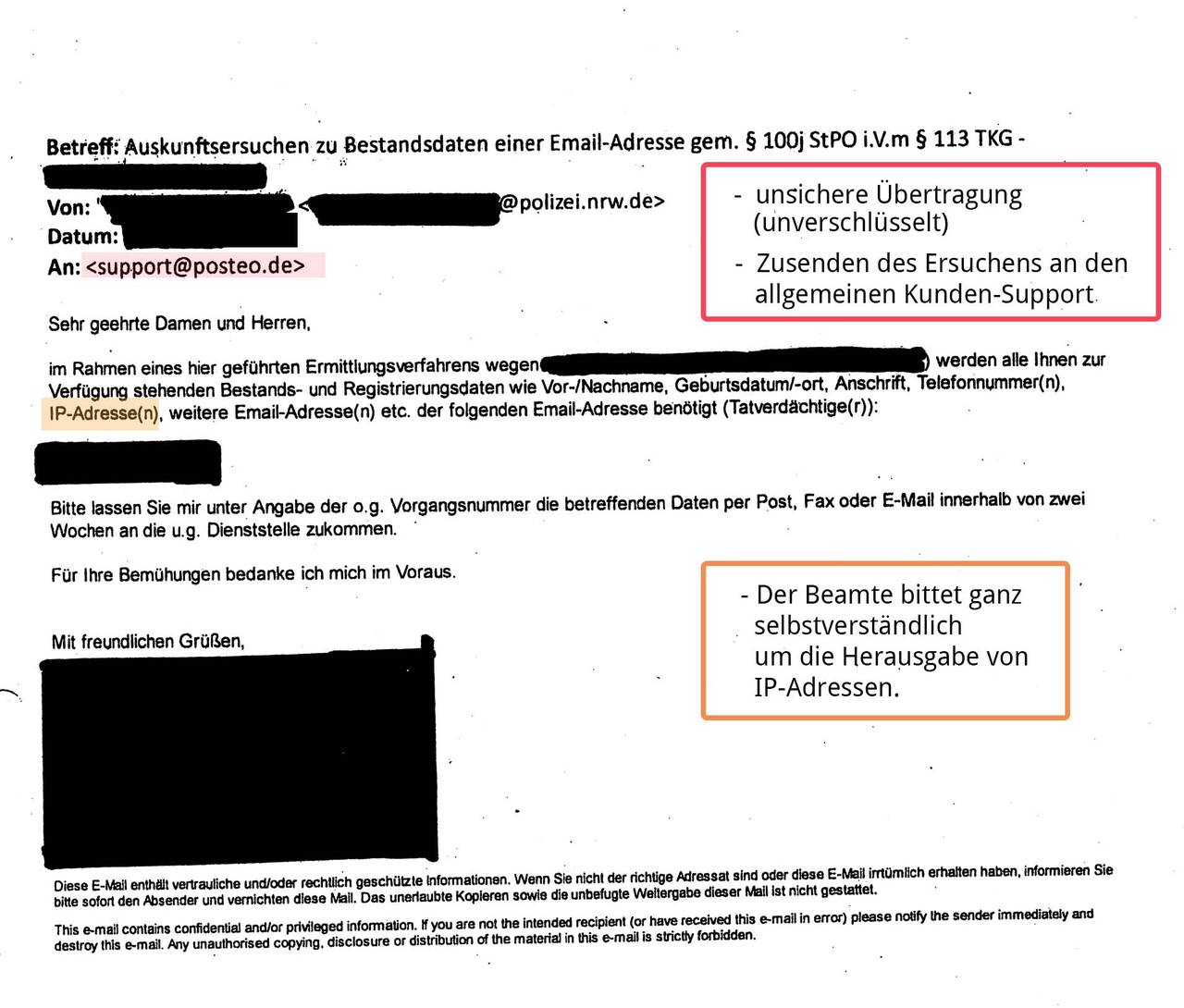

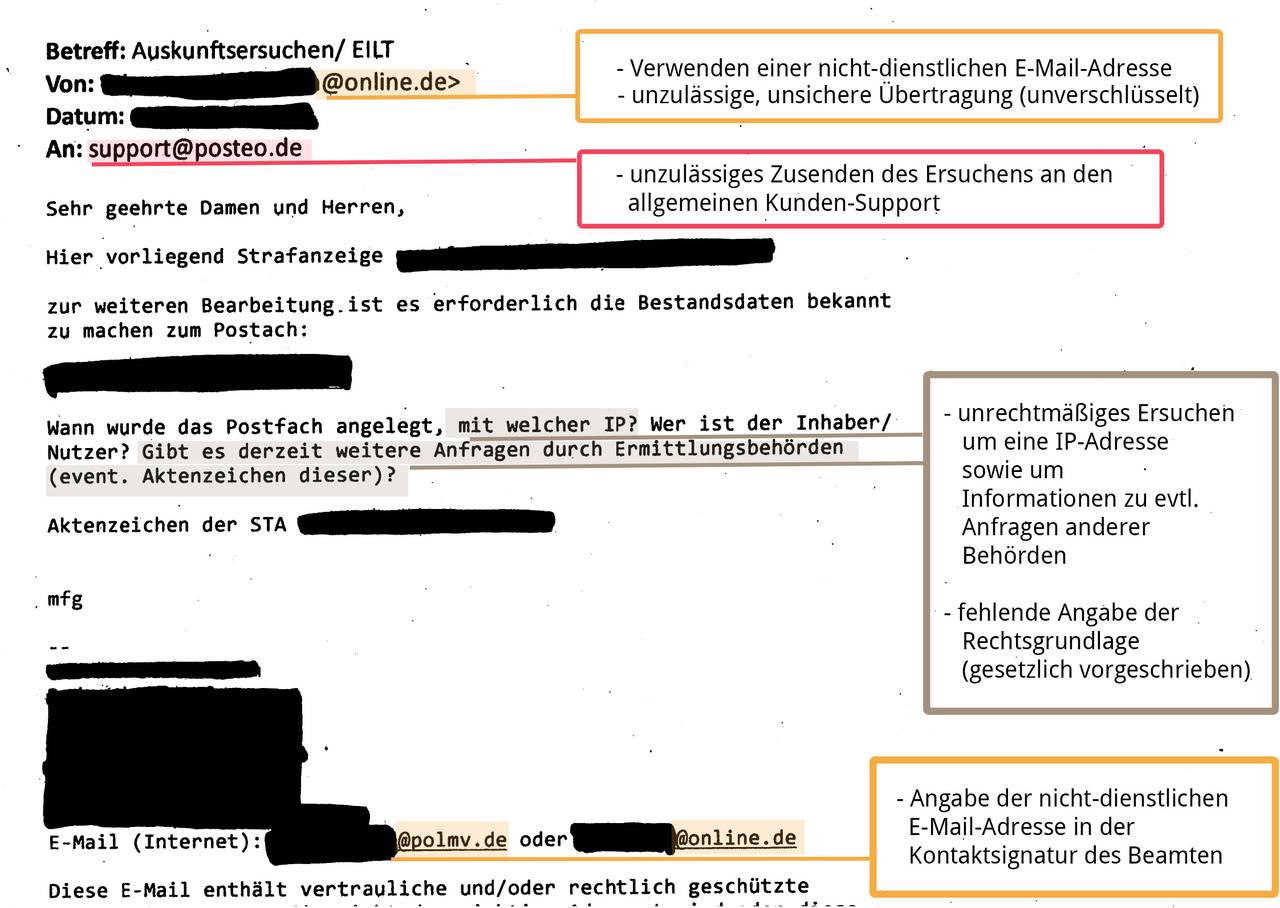

Many requests under § 113 TKG reach us via email and were transmitted to us insecurely or unencrypted. This procedure violates valid privacy provisions and is illegal. (See BDSG § 9, Anlage, sentences 4 and 8 as well as the respective rules on “technisch-organisatorischen Maßnahmen” of the Landesdatenschutzgesetze, among others). If requests are transferred unencrypted, they can easily end up in the hands of data thieves on their way over the internet.

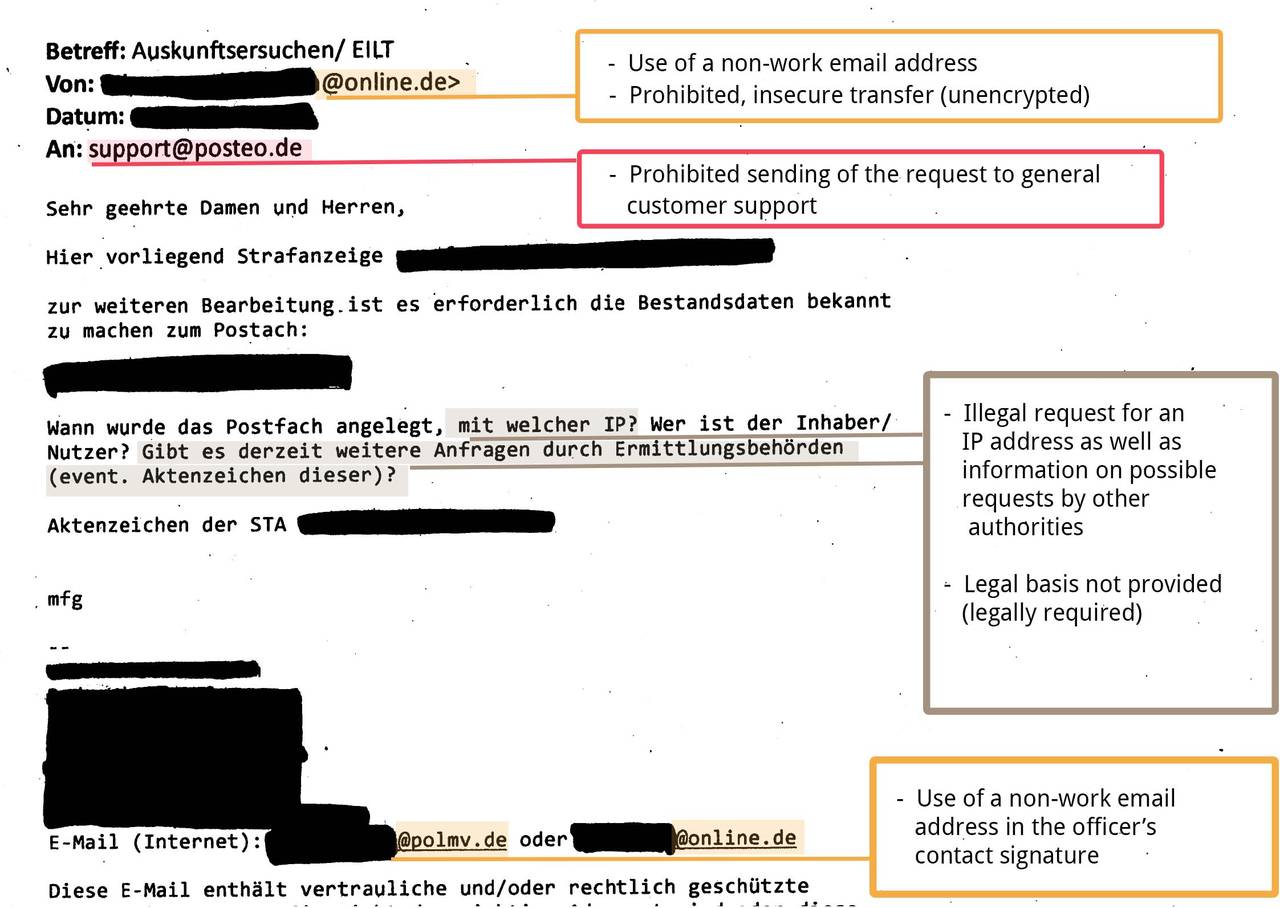

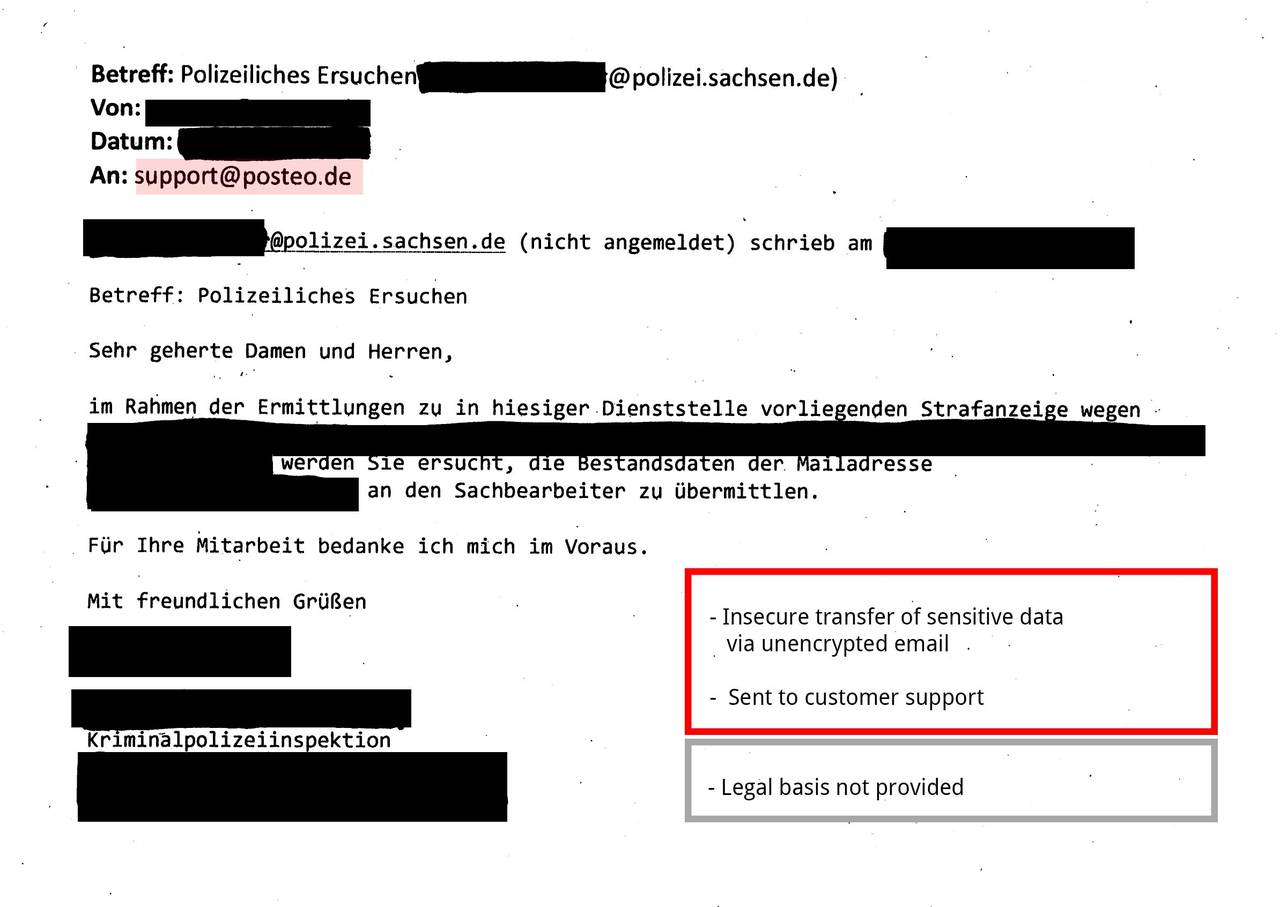

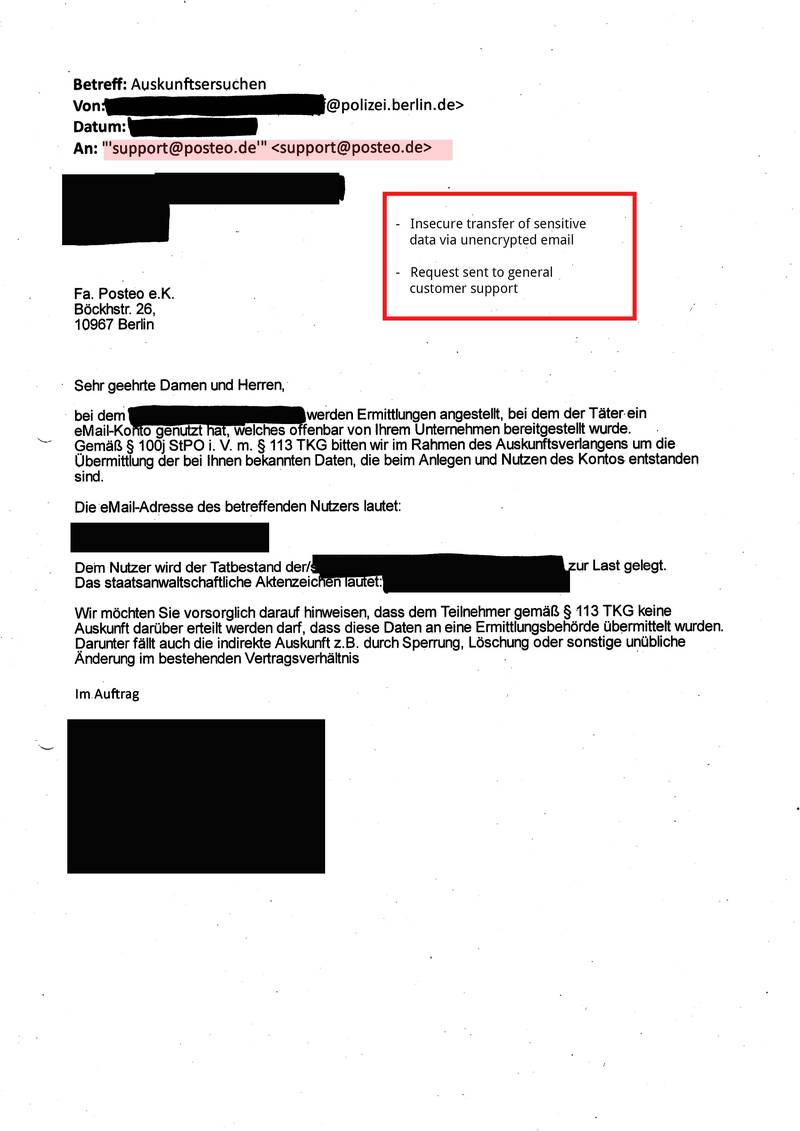

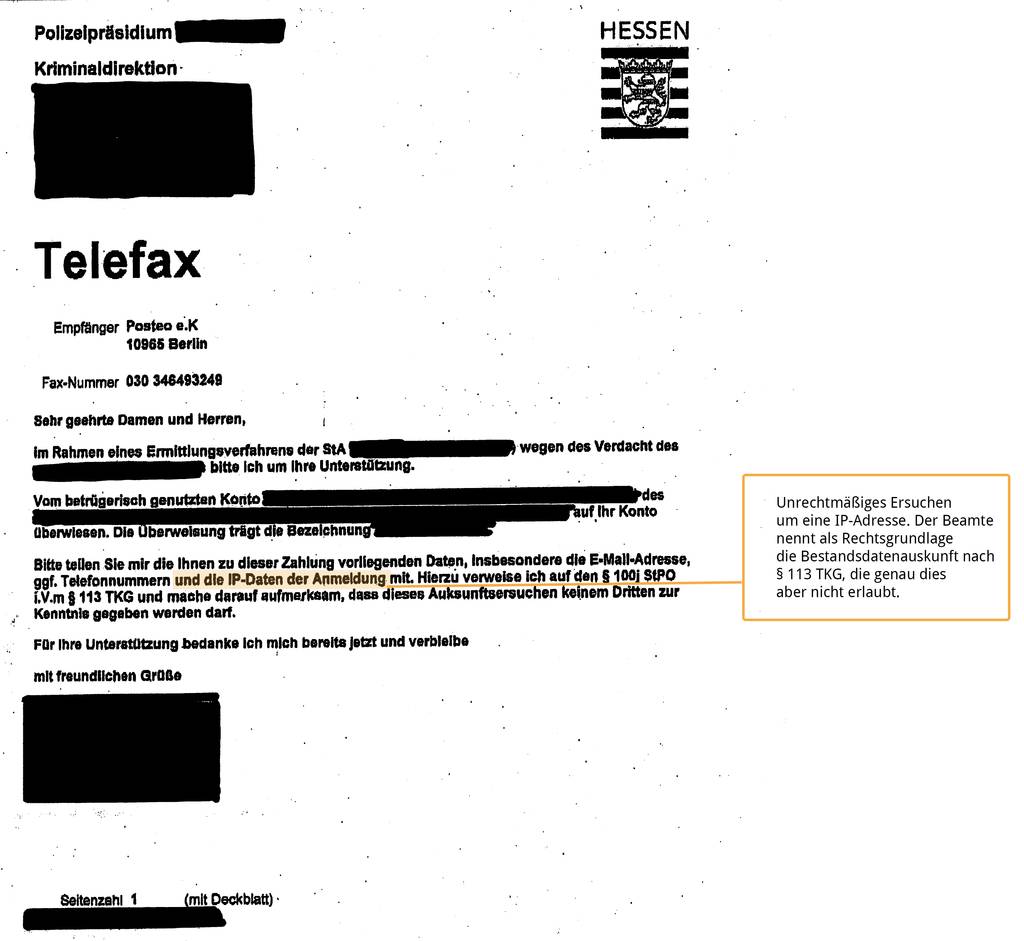

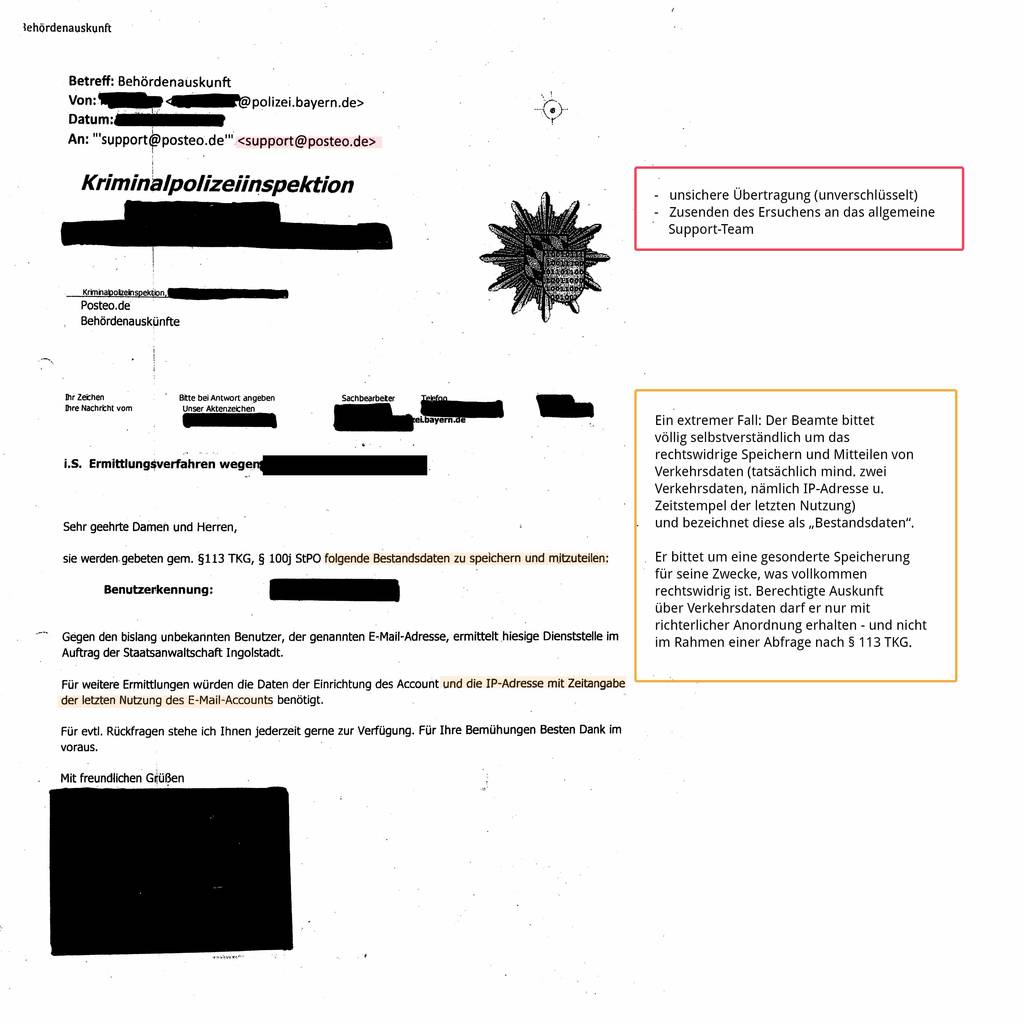

Many requests under § 113 TKG exhibit additional deficiencies that also violate privacy provisions or other laws. Some examples include:

- Sending police requests to our customer support rather than the people responsible (anti-abuse team)

- Use of non-work email accounts to transfer requests, providing such accounts as a reply address

- Requests for information and data, the release of which is not permitted under § 113 TKG, e.g. traffic data such as IP addresses

- Failure to provide a secure method to reply

- Failure to provide a legal basis for the enquiry (required by law)

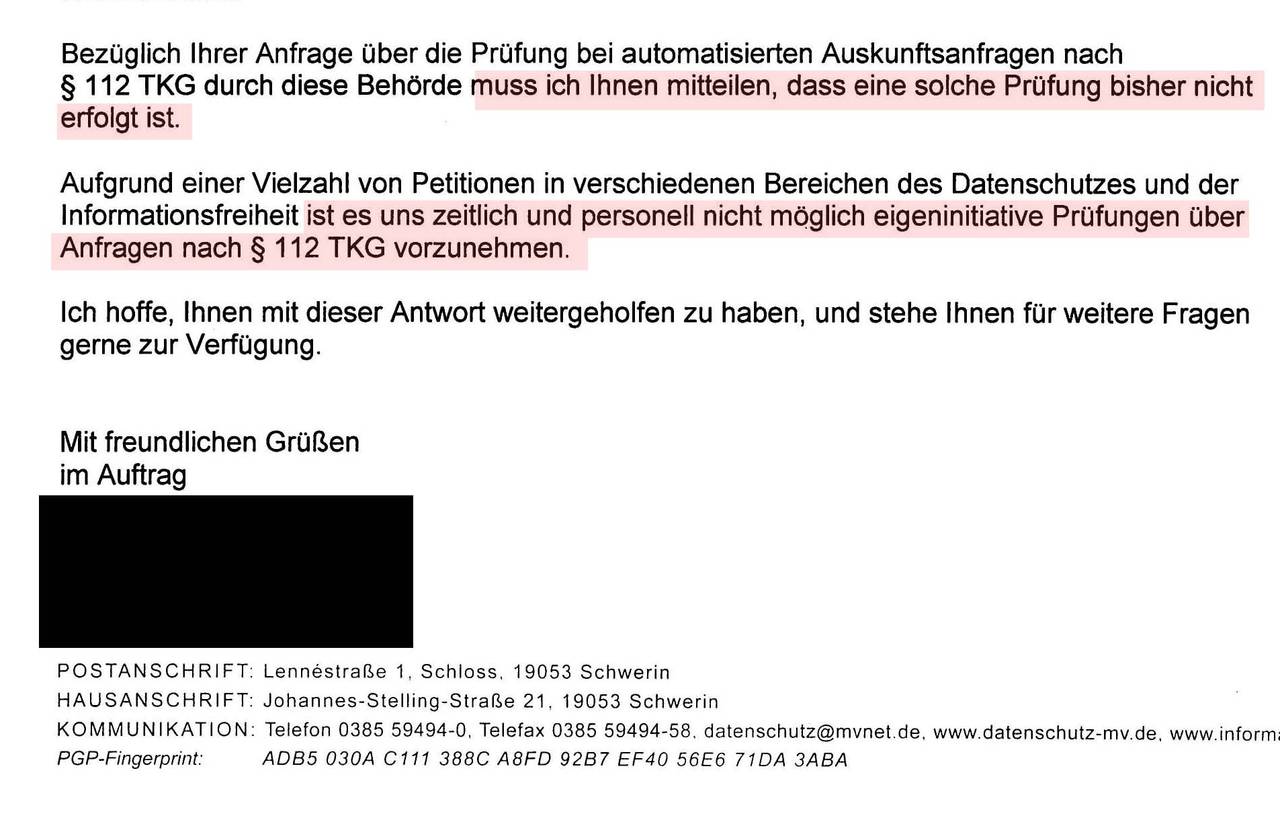

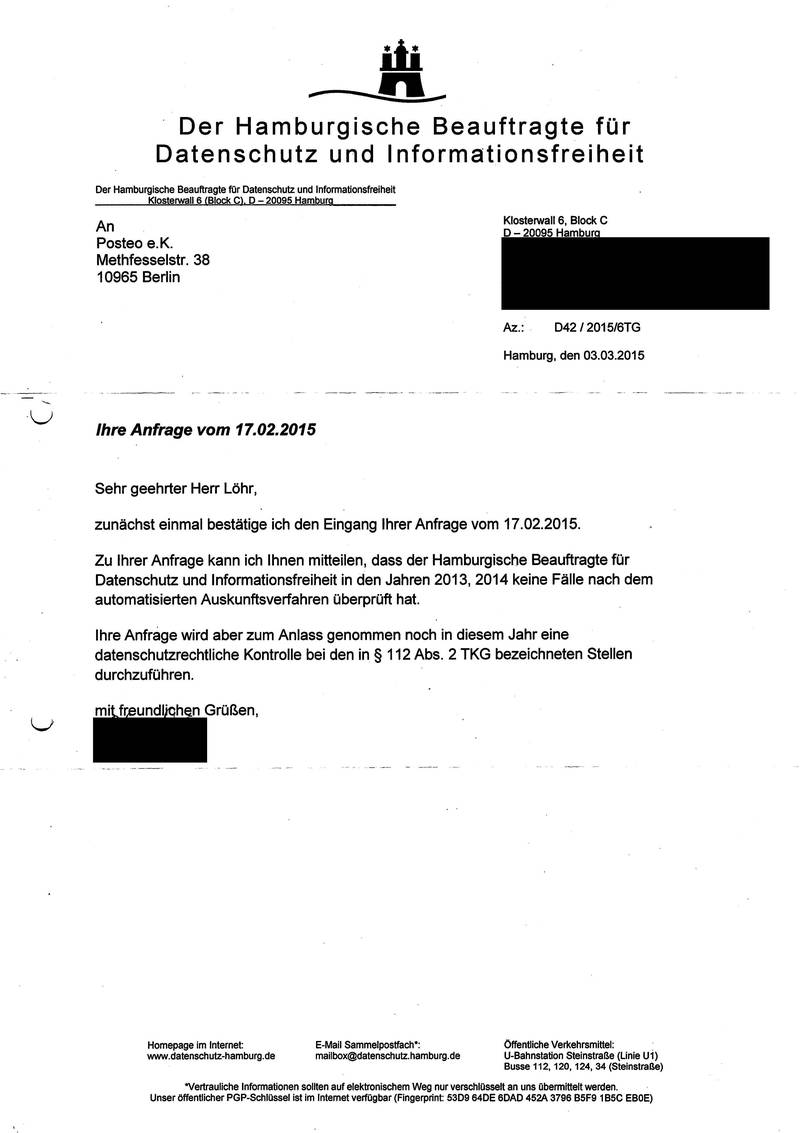

A large proportion of requests under § 113 TKG reach us in this way (by unencrypted email). Fax is seldom used by authorities (2013-2016), and only one single request has reached us so far by post. Occasionally, we also receive requests by email with an unencrypted document attached that is incorrectly marked "Telefax-Nachricht" (Telefax message). In January 2015, we first made complaints with the responsible privacy officers for the respective German federal states about the insecure transfer of sensitive data by police authorities. The responses from the privacy groups were unambiguous: the problem of insecure transfer of sensitive data by police authorities is known and remains an occasion for conversations and controls. The replies prove that insecure sending of sensitive information by police authorities is a topic requiring urgent action.

Here is what the privacy officer for North Rhine-Westphalia wrote to us:

[translation] Regarding the MIK NRW we have repeatedly advised that requests in investigative processes should in principle occur by post or in justified cases by fax. If a request by email is required in an exceptional case, either the message itself must be encrypted or as a minimum the transfer of personal information must occur in an encrypted attachment. I will treat your request as an occasion to raise this topic again with the MIK NRW to work towards a privacy-legitimate configuration of police investigations.

(Complete response in German: see gallery 2, below)

The Bavarian privacy officer informed us:

[translation] Since the transfer of personal information in unencrypted emails by the police continues to be an occasion for checks in terms of data-protection law, I have already concerned myself with this topic within my professional duties on multiple occasions. (…) I can assure you that I also regularly debate this topic independently of my concrete controls of the responsible police positions. I am currently in contact with the Bavarian State Office of Criminal Investigation to check the configuration of the retrieval process used there with telecommunications services.

(Complete response in German: see gallery 2, below)

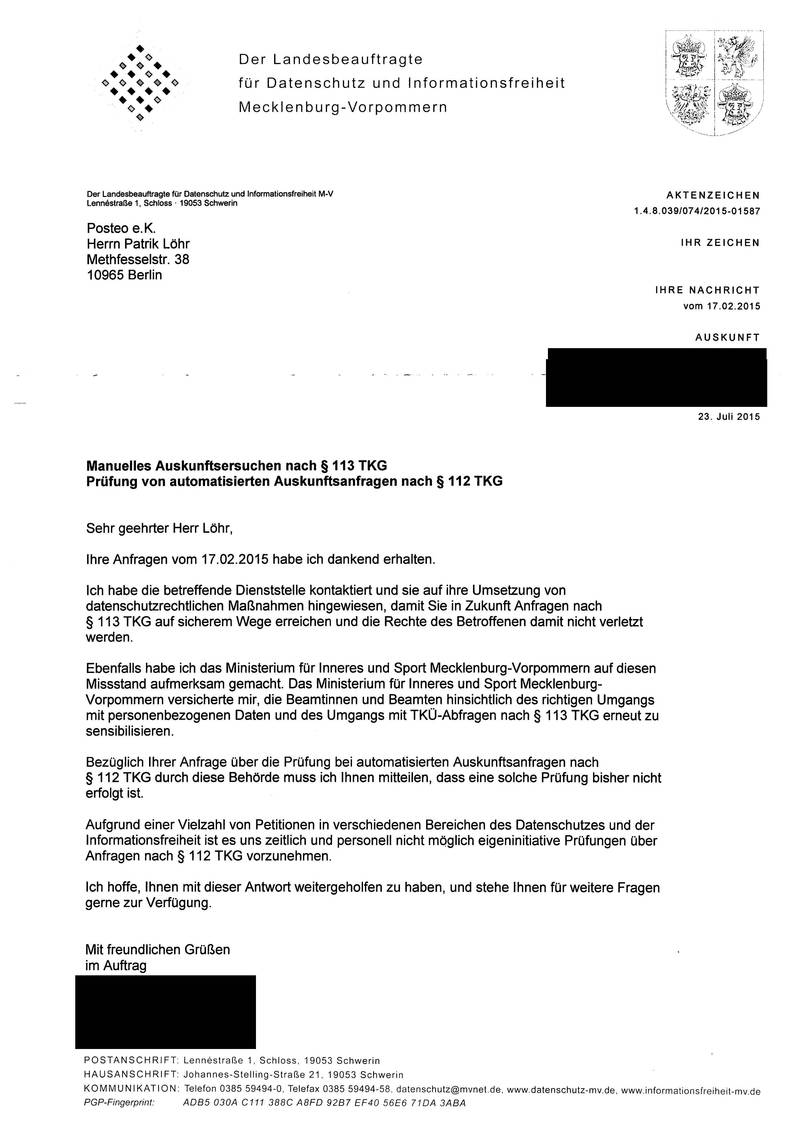

The Mecklenburg privacy officers were also active:

[translation] I have contacted the affected service post and referred to their implementation of privacy measures, so that in future requests under § 113 TKG arrive by secure means and the rights of the party involved are not violated. I have also made the Ministry for Internal Affairs and Sport of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern aware of this grievance. The Ministry (…) assured me that it would again sensitise the officers to the correct handling of personal data and surveillance (TKÜ) requests under § 113 TKG.

(Complete response in German: see gallery 2, below)

The Saxon privacy officers even set the police president an ultimatum:

[translation] We absolutely support your concern. I therefore today sent a letter to the Saxon police president with a request to redress this, and asked him to tell us by the 15th of April 2015 which remedies he has put in place.

Complete response in German: see gallery 2, below)

The privacy officers’ responses prove that unencrypted requests are a known problem to them. If it is common practice for police authorities to send sensitive information unencrypted via the internet (for example regarding requests under § 113 TKG), then it is not only a problem in terms of privacy: it is also illegal and possibly endangers current investigations. Data thieves can thereby easily access the requests or the authorities’ communication.

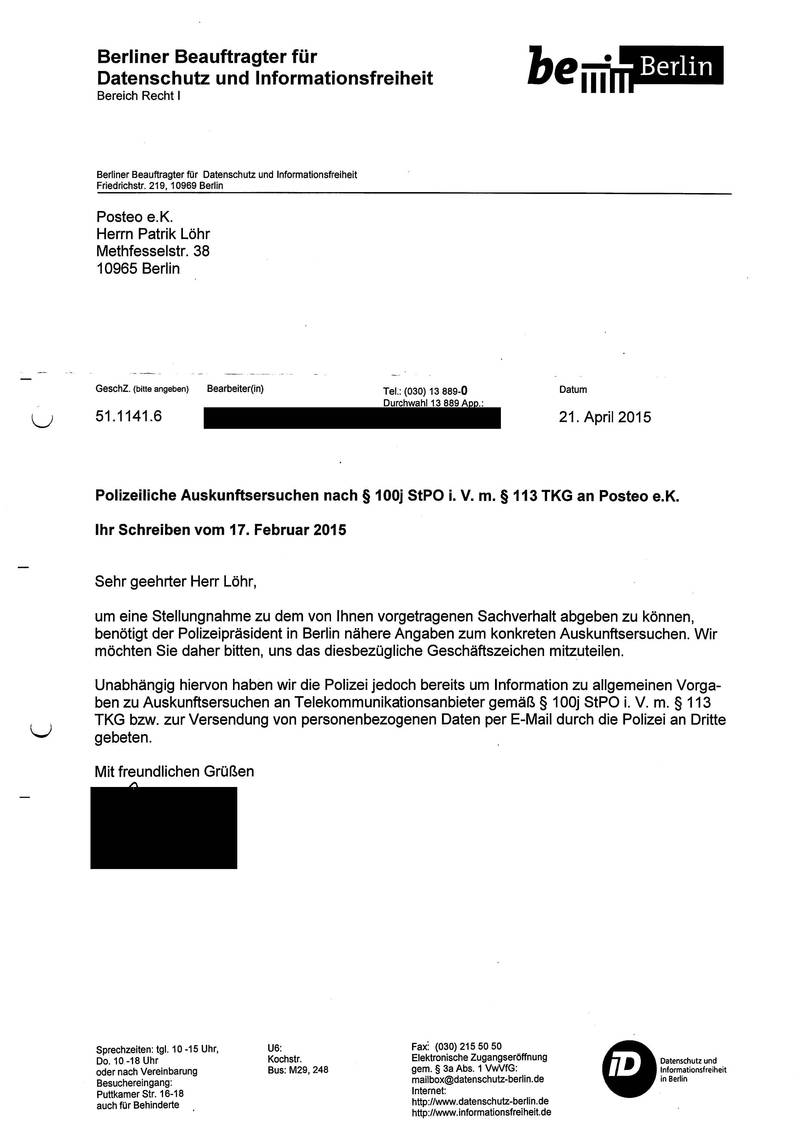

In some cases, we have experienced the bureaucracy as being very cumbersome. In response to one case, the Berlin privacy officer replied to us five months later, as follows: [translation] Unfortunately, the matter can not yet be conclusively resolved.

Some months earlier, he had notified us in writing that he had asked the police for information on current guidelines for requests for information and the sending of personal information.

In conclusion: we assume that total, nationwide security problems exist in the practice of manual requests for user information (under § 113 TKG). At Posteo, in any case, not a single request was received from police authorities by email that was encrypted and thereby conformed to the legal requirements for secure transfer.

Responses from the privacy officers have confirmed to us that we are not the only ones affected.

Unfortunately, our complaints have not yet led to any remedies. During 2015 and 2016, all requests that arrived with us via email were transferred insecurely, including from German federal states where the federal state privacy officer appeared particularly engaged. We are therefore asking ourselves how remedies can be achieved. If officers are not sufficiently schooled in secure ways of dealing with data and IT engineering, this constitutes a fundamental security problem in the police’s work.

We will continue to give the privacy officers regular practical feedback and inform them of every unencrypted transfer of a request that reaches us.

As we see it, the security of the process in practice is currently not guaranteed. We therefore engaged politics. Ultimately, however, it is not the provider’s task to check if the dealings of authorities are legal or to work towards this. The state itself needs to achieve and ensure that. In July 2015 at an appointment in the Posteo lab we gave Thomas Oppermann, chairman of the SPD fraction, a statement on this. Oppermann then wrote to Federal Minister of the Interior, Thomas de Maiziere. In his reply to Thomas Oppermann, the minister admitted to braches of the law in the practice. He explained, however, that the BKA would only desire user information in plain text if no encryption was possible for the email communication with a provider or if it did not support the methods used by the police authority. These statements by the minister are remarkable. He clearly considers breaches of the law to be justified in some circumstances. In addition, his statements do not apply: we provide the keys required for secure communication on our website, for example. Encrypted communication with us is unquestionably possible. Nonetheless we have received multiple requests from the BKA that were all transferred unencrypted. Every insecure transfer is a breach of the Federal Data Protection Act (BDSG). Criminal investigators must ensure that personal data can not be read, copied, changed or removed in an unauthorised manner during its electronic transfer, transport or saving to data storage. If a provider does not offer any possibility for encrypted communication, then fax or the post is to be used. The security of authorities’ communication must urgently be improved – otherwise, data thieves and hackers can easily obtain it.

In introducing the next problem area that we see in the practice of requests under § 113 TKG, we remain in political territory. In January 2013, SPD representative Burkhard Lischka directed a written enquiry to the German government. He asked whether it was known to the government,

[translation] that in practice, countless requests for the release of information under § 113 TKG have as their object the release of data that is not user information (e.g. log files, dynamic IP addresses, (…).

Questions to the government, from p7, q12, 13, 14 (in German)

He added: [translation] If so, which authorities conduct this illegal practice and what is the government doing to stop it?

The background to his question is that a few months earlier, BITKOM made the German parliament’s judiciary committee aware of grievances in requests for user information, in a statement:

[translation] In practice, countless requests for information under § 113 TKG are known that involve the release of data that does not constitute user information (e.g. log files, IP addresses, date and time of the last access to an account, addresses with other providers of the individual concerned, the identity of authorities that had already requested the same user information, etc). It therefore follows that providers already have to deal with countless requests that serve investigations and go far beyond the regularly content of the norm.

BITKOM statement from 17th October 2012 (in German)

To summarise, BITKOM objected that authorities making requests for user information (under § 113 TKG) frequently request information whose release in response to such requests is absolutely not lawful. For requests under § 113 TKG for which no judicial ruling exists, authorities can only request user information – approximately only names and addresses, and not dynamic IP addresses or log files. These highly-sensitive traffic data are governed by secrecy of telecommunications (Fernmeldegeheimnis) and can only be released at the directive of a judge.

In its reply on the 28th of January 2013, the German government dismissed BITKOM’s statements as “allegations”:

[translation] The government is – aside from the allegations quoted in the question of the BITKOM statement – not aware of any such cases.

Response from the German government (in German, from p7, q12, 13, 14)

The government nonetheless took the BITKOM accusations as an occasion to question various investigative authorities. And they stated:

[translation] The results of the interrogation did not provide any evidence of illegal requests.

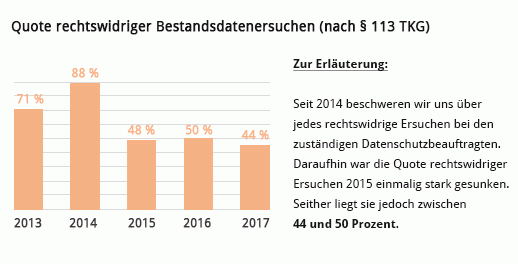

We hereby confirm the BITKOM “allegations”: in about 30% of all requests from police authorities that reached us in the years 2014 to 2016 concerning requests for user information under § 113 TKG, police officers illegally asked for dynamic IP addresses or the IP address of the most recent login.

To prove this, we continue to publish examples of such illegal requests (blacked out): the originals are located in writing at Posteo. In these, it is also clear that officers do not only attempt the illegal release of IP addresses, but also occasionally succeed to obtain and save these for their investigations. This is also not permissible.

We find it astounding that in January 2013 the government obviously did not via BITKOM turn to the organisation where such illegal requests exist. The government would, in our view, have informed itself with the organisations and needed to reach suitable remedy measures. That it refrained from doing this, even though it was informed by a large German industry association of illegal practices by authorities, is completely incomprehensible to us. Instead, clearly only the authorities were asked and the statements from the high-tech industry association were labelled allegations. In a constitutional state, when advice of illegal practices of the executive authority exist, these should be more seriously pursued.

In the summer of 2015, member of parliament Dieter Janecek (speaker on economics from the Greens fraction) again asked the government about this topic, wanting to know if they remain faithful to their assessment. In his question, the representative referred to the BITKOM statement as well as the Posteo transparency report.

The Federal Ministry of the Interior explained in its response:

[translation] The government still has no indication of any illegal requests. (…) Usually, the responsible entities for privacy controls educate senior authorities about offences against privacy regulations that have been identified. In the government’s view, proceedings beyond this are not required.

Response from the German government from 19th August 2015

Perhaps there is a communication problem between the privacy officers and the government, because in all cases in which police authorities illegally requested IP addresses, we made complaints to the respective federal state privacy officers. In their replies, none of the privacy officers responded to our complaints on this matter. Our complaints were clearly not passed on to the highest federal authorities, as is otherwise customary according to the BMI statement. Illegitimate requests for IP addresses do not constitute mere violations of privacy guidelines; requesting an IP address within a request for user information is illegal under the TKG law (Telekommunikationsgesetz). Those involved are not only federal state police authorities. We have also received such illegal requests requests from state investigative authorities.

Our conclusion: The government is clearly completely uninterested in whether illegal practices exist in requests for user information. The Federal Ministry of the Interior has remained idle for years. As such requests frequently infringe on citizens’ rights, this is irresponsible, in our view.

In cases of enquiries under § 113 TKG made to Posteo which illegally requested traffic data, situations subsequently often arose in which we were put under pressure and threatened. We always refer officials back to the valid law. We advise that we would make ourselves liable for prosecution by releasing traffic data in response to a request under § 113 TKG (see § 206 StGB) and that for the release of traffic data, a judicial ruling must exist. We explain to the officers that in a request under § 113 TKG, they can only request user information if they have an IP address on hand that is already known to them. The fact that the reverse disclosure is not allowed is often not known to officers.

Some react to this information with amazement or anger. Officers have repeatedly asserted to us that with other parties, they easily obtained IP addresses in requests under § 113 TKG. Whether this is true or was only intended to unsettle us, we don’t know. What we can prove is that police officers frequently and with great self-assurance make written requests for traffic data under § 113 TKG (see image gallery with examples). We therefore think that it is absolutely possible that the legislation on information practices is also not always observed by the obligated parties (e.g. companies).

One possible reason for this could be that the circle of parties regarding information under § 113 TKG is very large, and not restricted to telecommunications providers. Many of the obligated parties do not necessarily possess the required legal knowledge to be able to correctly identify illegal enquiries as such.

Due to escalated, illegitimate demands for IP addresses, we have already incurred enormous legal costs and financial damage of a mid-range, five-figure sum, for example, to lodge protective texts with the courts, for correspondence with investigating officers, legal advice, etc. In one case, we reported investigating officers who personally sought us out in our office. The public prosecutor’s office gave our notification no weight – as our lawyers had in advance predicted would happen. The prosecution told us that our document was plainly false and ceased any proceedings against the officers without any further investigations into them. Instead, they required us to pay a fine due to “false suspicion”, which the court also approved. Posteo company director Patrik Löhr was required to pay a fine. High legal costs are accompanied by the fact that we could theoretically receive 18 EUR back from the state for the effort involved in each request for user information under § 113 TKG. We do not make use of this facility. As a privacy-oriented company we do not accept any money from authorities for requests for user information.

We have shown that the security of the process is currently not guaranteed and that authorities frequently make illegal requests under § 113 TKG to Posteo for traffic data such as dynamic IP addresses. In addition, we have shown that the problem of insecure transfer is known to the respective German federal state privacy officers. Further, we indicated that the industry organisation BITKOM had in 2012 already made the government aware of countless illegal requests made under § 113 TKG.

Given the lack of process we would like to advise that the process under § 113 TKG with data retention ("Gesetz zur Einführung einer Speicherpflicht und einer Höchstspeicherfrist für Verkehrsdaten") will gain importance. The law will effect a large increase in the amount of data available for requests for user data.

Via the process, authorised parties will in future far more often be able to receive information about which person a dynamic IP address was assigned to at a particular point in time. An example: an officer approaches a provider with an IP address and would like to know which person is behind the address. The provider compares the IP address with the IP data that are held in their database for data retention. This is allowed for the provider without a judicial ruling. The provider must then tell the officer which person is behind the IP address (again: not the other way around). This is very coveted information for which no judicial reservation is intended and can already be used in cases of minor breaches of the law.

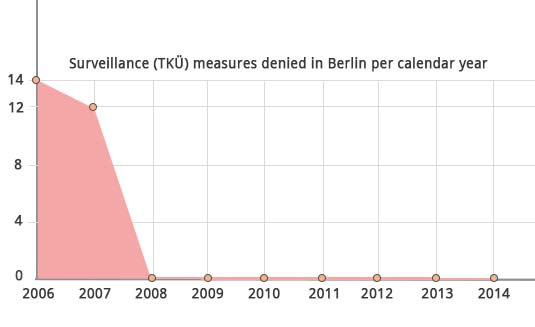

We therefore assume that the number of requests under § 113 TKG and thereby also the number of insecure and illegal requests will sharply increase with the introduction of the new law. There is an additional reason for this assumption: checking IP data and the resulting release of user information can only occur via the manual disclosure process under § 113 TKG. This is not possible via the automated process under § 112 TKG.

It is our view that the process under § 113 TKG with its current patent flaws in practice is in no way suitable. Today a large amount of citizens’ sensitive data is already insecurely transferred due to this process and there are countless illegal enquiries from authorities.

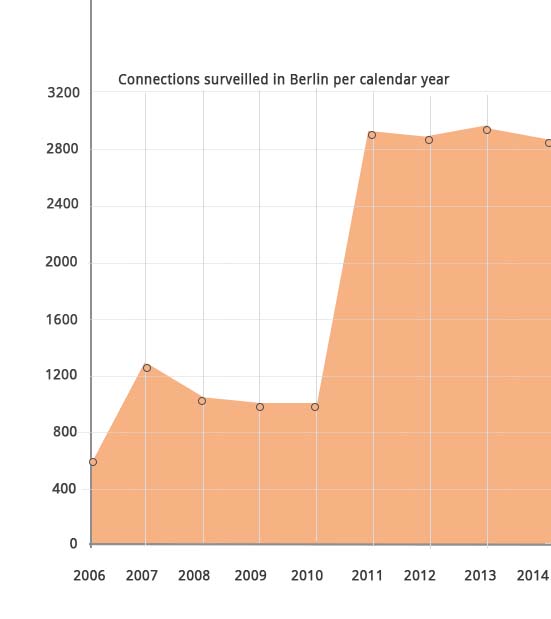

In addition, there are insufficient controls of the process: to our knowledge, there is no requirement in existence to keep statistics for enquiries under § 113 TKG. Thus the effect of the introduction of the law on data retention – how it concretely affects the number of requests – can not be evaluated, and the number of requests by state authorities will remain unknown to the public.

It is in no way acceptable that citizens’ sensitive data continue to be sent or requested insecurely over the internet by authorities, or that dynamic IP addresses governed by the secrecy of telecommunications are given out in response to simple enquiries under § 113 TKG without a judicial ruling. In our view, no new laws or guidelines can therefore be introduced that would further increase the number of illegal and insecure requests made.

We therefore demand that the government introduces measures as soon as possible that are intended to ensure that the request and transfer of sensitive citizens’ information by authorities under § 113 TKG occurs fundamentally by secure means (no proprietary solutions) and also corresponding to the legal regulations – and when it occurs by email, then exclusively by encrypted email. In addition, we demand that the government introduces measures as soon as possible that ensure that for requests for user information, no more illegal requests for traffic data or any other information that goes far beyond the norm occur.

We are of the view that there is a glaring need for processes to be adjusted in an organisational respect, so that a privacy-equitable and constitutional state conforming configuration of the disclosure process can be secured in future. For this, we suggest the introduction of reporting requirements (among other things, see the section on controls of the information process).

Until this remedy is achieved, data retention (Einführung des Gesetzes zur Einführung einer Speicherpflicht und einer Höchstspeicherfrist für Verkehrsdaten) is in our view unreasonable for this reason alone, as it will in practice further increase the amount of insecure and illegitimate data transfer and the legal cracks in the disclosure process under § 113 TKG.

Independent of this, we completely and with great emphasis reject the reintroduction of data retention for countless further reasons, e.g. for privacy reasons and data security as well as due to its accompanying blanket restrictions of fundamental rights, that we do not deem reasonable. On this topic, please also read our text on the control instrument of judicial reservation, which we also criticise in this report. The law will nonetheless confront providers like Posteo with even more illegal requests and accompanying bureaucracy and legal costs in connection with requests under § 113 TKG.

In addition, we demand that the Federal Office for Information Security become liberated as an independent state authority from the business branch of the Federal Ministry of the Interior so that the BSI can be an independent contact for security questions.