Reporters without Borders: Crises and violence threaten freedom of the press

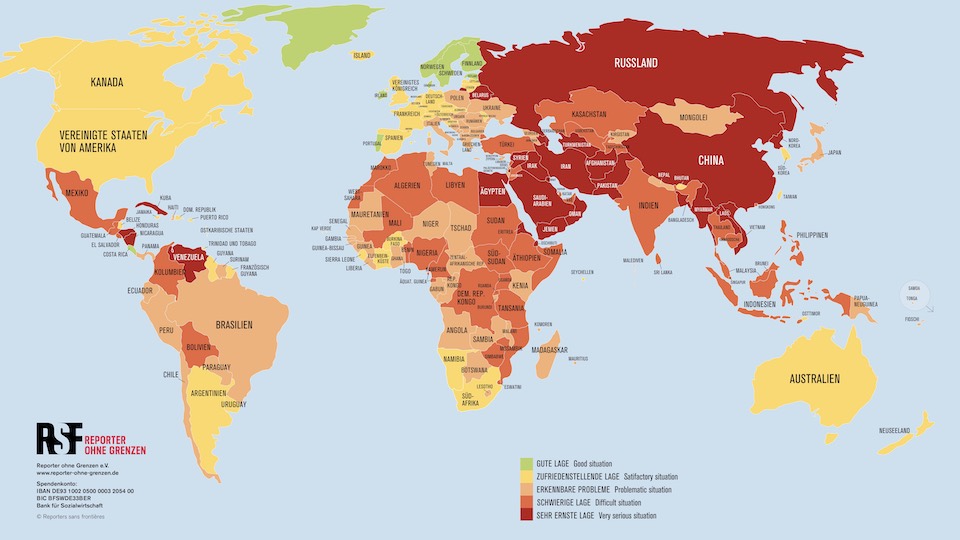

New crises and wars are threatening press freedom worldwide and have put media professionals at risk since the beginning of 2021. This was announced today by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) on the occasion of the publication of this year’s press freedom rankings. The ranking compares the situation for journalists and the media in 180 states and territories.

The global press freedom situation has been dominated by crises, wars and violence since the beginning of 2021, RSF said. For example, the junta in Myanmar made independent journalism virtually impossible after the military coup. Numerous media workers there were sentenced to prison. The country slips to 176th place out of 180 in the ranking.

In Afghanistan (156th), the Taliban takeover has made working conditions for media professionals extremely difficult. In all parts of the country, they are the target of intimidation and violence, and open censorship prevails. Women are particularly affected: Four out of five female journalists have given up or had to give up their profession (in German).

War in Ukraine

Russia has “de facto abolished” press freedom after the attack on Ukraine. The country now occupies 155th place in the ranking. Already last year, many journalists and editorial offices had stopped working after being declared “foreign agents” (in German). Then, after the invasion of Ukraine, the Russian media regulator had banned words like “war” and “attack” in reporting. Disseminating alleged false information about the Russian army carries a penalty of up to 15 years in prison. According to RSF, hundreds of independent journalists have since left the country. Media critical of the Kremlin have ceased their work.

In Ukraine (ranked 106), the situation has deteriorated since the Russian attack. At least seven media workers were killed there in the first two months of the war. The Russian army has deliberately fired on media teams. Journalists have been abducted by Russian soldiers or their relatives pressured to silence them.

“Murders and kidnappings, arrests and physical attacks are just different manifestations of the same problem: governments, interest groups and individuals want to use violence to prevent media professionals from reporting independently. We observe this phenomenon in all parts of the world, whether in Russia, Myanmar or Afghanistan – or even in Germany, where aggressiveness towards journalists has risen to a record high,” said RSF board spokesperson Michael Rediske (in German).

Freedom of the press in Europe

Europe continues to be the region of the world where journalists can work most freely, in comparison. However, RSF has also observed increasing violence against media workers there in the past year. The murder of the crime reporter Giorgos Karaivaz in Greece and the well-known police reporter Peter R. de Vries in the Netherlands were tragic culminations.

RSF criticises that the murder of Karaivaz has still not been solved. In addition, media workers in Greece have repeatedly been prevented from reporting on controversial topics such as the situation of refugees on the Greek islands. There are “regular” attacks on editorial offices by right-wing and left-wing extremists. A new fake news law (in German) also increases the danger of self-censorship. This year, Greece replaces Bulgaria (ranked 91) as the worst-ranked country in the EU, coming in at 108th place.

The Netherlands used to be among the ten best-ranked countries, but now, due to the murder of de Vries, it has slipped to 28th place. Traditionally, freedom of the press has been a high priority in the country and is protected by laws, the state and the authorities. However, attacks on media workers and editorial offices have also occurred in the past and recently verbal aggression on and offline has increased.

The situation in Germany has also dropped by three places – to 16th place. RSF justifies this mainly with violence against media workers during demonstrations. With 80 verified cases, the number of assaults last year was higher than ever since the documentation began in 2013. Most of the attacks had occurred during protests against the Corona measures: Media workers were spat on, kicked or beaten unconscious. In addition, 12 police attacks on press representatives were documented. Journalists have also been attacked at home, in courtrooms and in football stadiums. RSF also assumes that the number of unreported cases is high.

The organisation also criticises legislation in Germany that endangers media workers and their sources. This includes, for example, the amendment to the constitutional protection law passed in June 2021, which for the first time allows all German intelligence services to use spyware to monitor communications (in German). Last October, RSF filed a lawsuit against this authorisation (in German), seeking a ban on the use of spyware against “unsuspicious bystanders” such as journalists.

In Germany, moreover, the diversity of daily newspapers continues to decline. Economic problems had been exacerbated by the Corona pandemic.

Within Europe, apart from Germany and the Netherlands, France (26th) and Italy (58th) in particular experienced a number of violent attacks on members of the press.

Poland (66th) has a diverse media landscape. However, the government has repeatedly tried to influence the editorial line of private media (in German).

RSF describes the situation of press freedom in Turkey (ranked 149) as “catastrophic”. Ninety percent of the media are state-controlled, the internet is systematically censored, and the judiciary is misused to silence journalists. Two media workers were murdered there in early 2021.

The situation in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa is also worrying: several journalists were killed or deliberately murdered in the course of their work there in 2021. For example, in Lebanon (ranked 130), journalist Lokman Slim was found dead next to his car in February. RSF writes that the Hezbollah critic had a bounty on his head. In Yemen (rank 169), reporting is also often life-threatening. In Aden, the country’s fourth-largest city, three reporters died in explosions.

Tunisia, at 94th place, is still the best country in the region. Freedom of the press and information were achievements of the 2014 constitution, but concerns (in German) arose when President Kais Saied took power in July 2021 and declared a state of emergency.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the situation of press freedom is extremely heterogeneous. South Africa (rank 35) or Senegal (rank 73) have a diverse media landscape. In countries like Djibouti (ranked 164), on the other hand, there is no room for a free and independent press.

Intimidation campaigns in Latin America

RSF describes the working environment for journalists in most Latin American countries as “increasingly toxic”. Anti-media rhetoric from politicians is fuelling distrust of the media in Brazil (ranked 110), Venezuela (ranked 159) and El Salvador (ranked 112), among others. There are smear and intimidation campaigns, especially against female journalists.

In Mexico (ranked 127), at least seven media workers were murdered last year. For the third year in a row, it is the “deadliest country in the world” for journalists.

Costa Rica is an exception in the region. The country ranks 8th and is a unique case in the Americas, according to RSF.

Hong Kong saw the biggest drop in the press freedom rankings, falling from 80th to 148th place, while China (ranked 175th) extended its model of information control (in German) to the Special Administrative Region. Hong Kong was once a bastion of press freedom, but now editorial offices are being closed and media workers arrested.

Scandinavian countries at the top of the list

At the top of the ranking is Norway for the sixth time in a row. It is followed by Denmark and Sweden. Estonia (rank 4) is the first former Soviet republic among the top five countries. Politicians there would not attack media workers; media companies had also reacted to online agitation with protective measures for their employees. Finland follows in fifth place.

The final group in the ranking is made up of totalitarian regimes. Turkmenistan, Iran, Eritrea (in German) and North Korea are ranked 177 to 180.

This year, twelve countries are in the worst category “very serious situation” – more than ever before. However, according to RSF, this is more to be understood as a trend. The ranking was compiled this year using a new methodology (in German), which leads to limited comparability. The ranking is now based on five new indicators: political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context and security. These are collected through a quantitative survey of attacks on journalists and a qualitative survey in which selected journalists, academics and human rights activists in the respective countries answer 123 questions.

According to RSF, the 2022 press freedom rankings reflect the situation from the beginning of 2021 to the end of January 2022. Since the situation in Russia, Ukraine and Mali has changed dramatically since then, developments up to the end of March 2022 were taken into account for these three countries. (js)